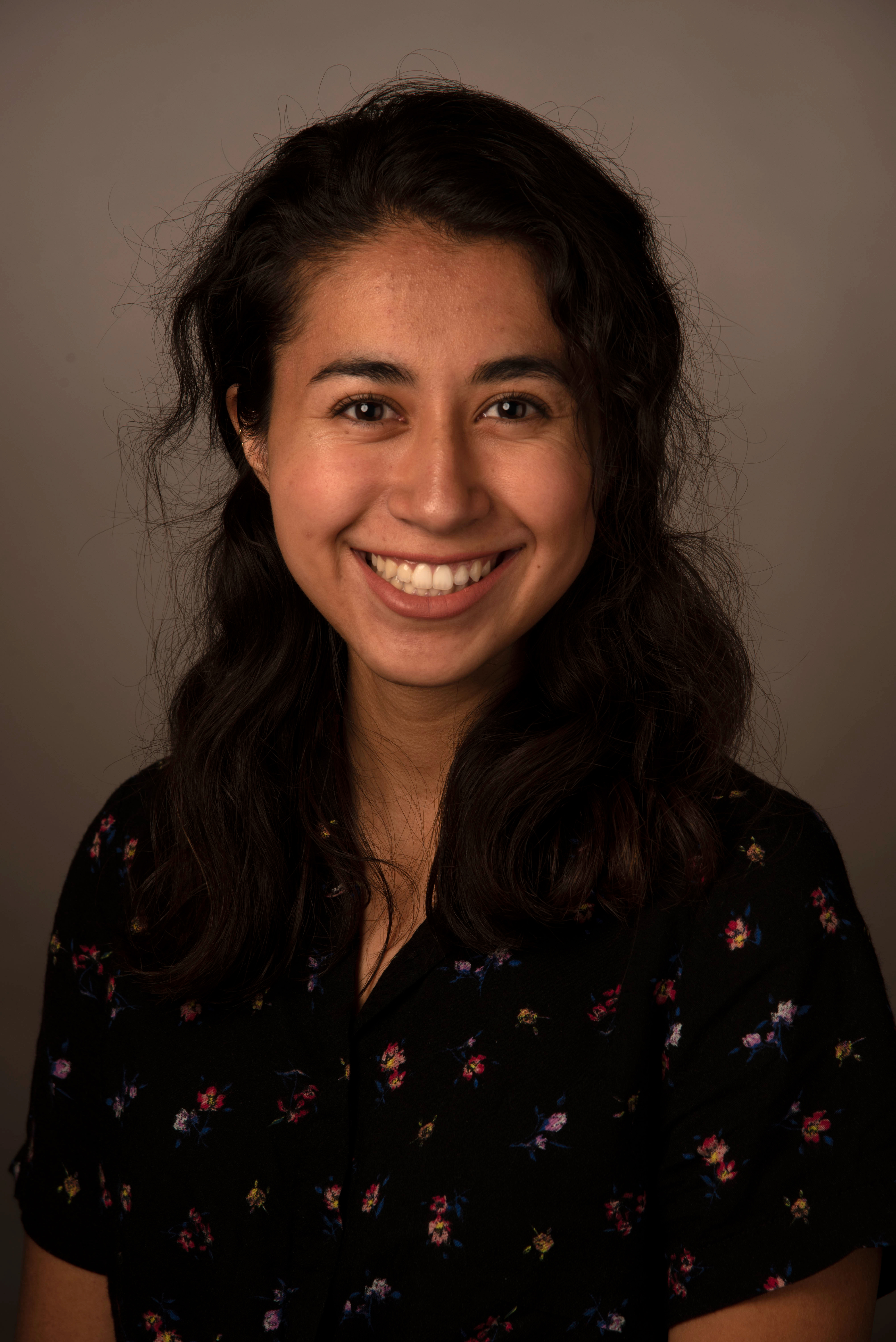

Cassandra Garibay is a journalism junior, current news editor and future managing editor of Mustang News. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of Mustang News.

My name is Cassandra Rose, a name carefully chosen by my parents, Hector and Blanca. One that sounds nice in Spanish, but does not immediately give away to potential employers that I am Latina, something their parents had not considered for them, my mom once told me.

But my name is not the only thing that could give way to potential discrimination.

In second grade, two boys told me I was the color of shit. And that is exactly how they made me feel. I didn’t tell my parents for weeks and thought it was my fault until one day I broke down and asked my mom why I didn’t have fair skin like her.

Now, it’s something I take pride in.

Since then, any incidents related to my race have manifested on a micro-level. And until my sophomore year at Cal Poly, I was able to ignore them, but now I am reminded on a near daily basis about the issue of diversity or lack thereof. Most days it leaves me exhausted and in that, I know I am not alone.

I grew up in a small, census-designated place, not big enough to be labeled a town. Madera Ranchos, sandwiched between Fresno and Madera, two minority-majority cities, is approximately 63% white according to July 2018 U.S. Census data.

I was one of the only people in my friend group in high school to have a Quinceanera, a bilingual home or a large family. Despite these differences, I had a great childhood.

From time to time I would question if so-and-so’s parents didn’t want their kids to hang out with me because I am Mexican, but my parents told me not to pay mind to that.

I heard rumors that one of the few Black students at my high school switched schools because a drawing of a person of color being hanged was left in his locker, but it was never addressed to the school as a whole.

So going into Cal Poly, I didn’t fear a culture shock. I wasn’t worried about being a minority on campus because that was how I was raised. And my parents always told me to push past that, to do my best regardless of people’s perception.

Fast forward — past the fact that I hadn’t heard Spanish my freshman year on campus until spring quarter, past the time someone assumed I was undocumented, past any and all other incidents I have long ago pushed under the rug and forgotten or laughed off — to the blackface incident.

I was an arts and student life multimedia journalist for Mustang News, but I always had an interest in news reporting. The day of the emergency town hall, the news editor at the time asked if I could switch from arts to news to help cover the events that followed the incident.

I didn’t realize the emotional toll that would come with it. At the town hall meeting, I heard many people bare their vulnerabilities to a crowded room.

And then I was tasked to go up and interview them in their moments of raw pain. Not for me, or for the benefit of Mustang News, but to share their experience and try to explain what yet another racist incident felt like to people who have never known what it is like to be told you are lesser because of the color of your skin. And after all, that is why I went into journalism — to share the experience of people whose stories are important and yet so often left untold.

Most interviews were declined, which I expected. But it was whenever I asked for an interview and someone responded with something along the lines of, “How are you handling this as a person of color?” I felt a mix of both gratitude and confusion.

While reporting on the blackface incident, I did not see myself as an affected person. I saw myself as a journalist, and as a journalist it was my job to remove my opinion from the matter. I would deal with my own emotions later.

But regardless of when I wanted to figure out my thoughts, I was put in a position of discomfort. Fundamentally, part of who I am is part of the hurting, affected community at Cal Poly. Another part of who I am and who I want to be as a journalist requires that I remain objective. (I was even nervous to write this editorial because I don’t want to compromise that, but after all, I can’t pretend to not have thoughts on an issue that gets brought up so often). And historically, the news media has not adequately or accurately covered minority groups, creating a general distrust or dislike. It may sound a bit confusing, because it is.

I could not help but feel a connection to some of the stories shared in the town hall meeting room. And at the same time, feel as though I was an outsider to the community.

I was told once while asking for interviews that if they decided to talk to any media, it would be me. I wondered if it was because they felt confident in my reporting abilities or because I wasn’t white.

When the dust settled a little, I realized for me, the blackface incident was not a breaking point, but an event that shined a light on all the subtle things I chose to ignore until then.

In the aftermath of the incident, I continually struggled with my role in it all. Is continuous coverage only causing people to relive hurt? Is my work hurting or helping?

It’s been a year now and I still re-assess my role as a Latina journalist with every story or conversation about diversity. And as many people have said before me, the conversation is not yet over. Moving forward I can only hope the conversation is less isolating and more empowering. This year and the next I will use my role in Mustang News to help bridge that gap through our coverage and conversation.