In April of 2018, a string of racist events on Cal Poly’s campus drew international attention and prompted the university to take action — from calling on California’s Attorney General to investigate the blackface incident, to establishing a $243,000 partnership with diversity specialist Damon Williams. Cal Poly’s ubiquitous lack of diversity was even found to persist in an otherwise diverse population: athletics.

A Cal Poly problem or an NCAA problem?

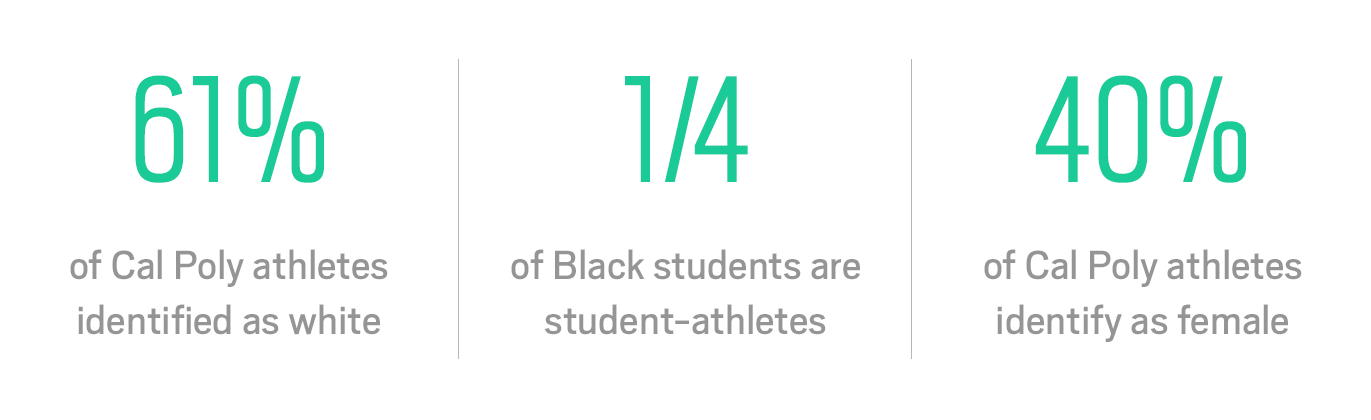

According to data released by the athletics department, 61 percent of Cal Poly student-athletes identified as white in the 2017-2018 academic year. White student-athletes accounted for 324 of Cal Poly’s 535 student-athlete total. This meant the percentage of white students in athletics was higher than the percentage of white students in Cal Poly’s total student body (54.8 percent).

Black student-athletes, on the other hand, accounted for only 8 percent of the student-athlete population. With a Black student body of 0.8 percent, the 44 student-athletes who identified as Black in 2017-18 represented more than a quarter of Cal Poly’s Black student body at the time.

Men’s Soccer senior Jared Pressley said the visibility of African-American males in athletics is deceiving to their actual representation.

Men’s Soccer senior Jared Pressley said the visibility of African-American males in athletics is deceiving to their actual representation.

“When I think of athletics, and I’m not trying to be rude to the other sports, but I think of the big teams like football and basketball, and I see a decent percentage of those teams are made up of African-Americans,” Pressley said. “So, I thought it was pretty equal within athletics. But, then I think of track, and here I am on Men’s Soccer where there’s not a lot of African-Americans, so I can see how it adds up.”

Cal Poly Athletics’ diversity problem, while not an anomaly, is worse than other NCAA counterparts. The NCAA Race and Gender Demographics Database reports demographic totals for divisions and conferences, but does not provide statistics for individual universities. Yet, in 2018, Black student-athletes accounted for 21 percent of the Division I student-athlete population — 13 percent higher than Cal Poly’s Black student-athlete population.

The Mustangs’ 20 Division I teams are primarily members of the Big West Conference. The Big West, comprised of Cal State Universities (CSUs) and Universities of California (UCs) similar to Cal Poly, also has better representation amongst Black student-athletes as a whole. In 2018, almost 14 percent of student-athletes in the Big West Conference identified as Black — 6 percent higher than Cal Poly’s Black student-athlete population. The Big West’s white student-athlete population sat just below 42 percent compared to Cal Poly’s 61 percent — a stark contrast.

Cal Poly is also far less diverse when it comes to women in sports.

The U.S. Department of Education Equity in Athletics Data Analysis (EADA) states females accounted for just 40 percent of Cal Poly’s student-athlete population in 2017-18. In the same year, women made up 47 percent of all NCAA Division I athletes. In the Big West Conference, that number increased to 53 percent.

What has Cal Poly Athletics done to increase diversity?

Though Athletic Director Don Oberhelman did not return a request for comment, it is clear the department is aiming to diversify its staff. On Dec. 21, 2018, Cal Poly Athletics promoted associate head coach Caroline Walters to the head coach position of the volleyball program.

About a month later, on Jan. 24, Cal Poly Athletics announced Sara MacKenzie as director of Strength and Conditioning. MacKenzie’s hiring made her just one of two women to hold the position for NCAA Division I schools with football programs.

On March 28, Cal Poly Athletics announced John Smith as the next Men’s Basketball head coach. Smith is currently the only Black head coach at Cal Poly.

Men’s Basketball senior Donovan Fields said Smith’s hiring should attract more minority athletes to the program.

“For a kid like me, I’m from New York,” Fields said. “Having a Black head coach, especially in Division I basketball, because along Division I there’s not that many, so for coach John Smith to get that opportunity here, I feel like that’s a really big thing.”

“Having a Black head coach, especially in Division I basketball, because along Division I there’s not that many, so for coach John Smith to get that opportunity here, I feel like that’s a really big thing”

Fields was right about the significance of Smith’s hiring. In 2018, Black head coaches held only 8 percent of NCAA head coaching positions. Without historically Black colleges and universities, that number falls to just 6 percent. In Division I men’s basketball, a sport dominated by minority athletes, only 27 percent of head coaches were Black. For Division I women’s basketball, Black head coach representation stood at 23 percent.

Representation does not improve when you move to Divisions II or III, either. The 2018 College Sport Racial and Gender Report Card by the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sports found that in Division III, African-American representation was so poor that the percentage of women coaching men’s teams was higher than the percentage of African-Americans coaching men’s teams (6.8 percent versus 4.9 percent).

How have the numbers affected the minority student athlete experience?

Pressley said he was unaware of Cal Poly’s lack of diversity before he arrived as a freshman in 2015. Fields also said he was unaware, as his official visit took place during the summer.

“I was thinking, ‘I’m going to California, I’m going to see everything in the rainbow,’” Pressley said.

However, during his first year as a Mustang, Pressley was just one of four Black players on the Men’s Soccer roster. During Fields’ first season with Men’s Basketball, he was one of three Black student-athletes on the team.

“It was hard at first, not being used to being the only Black kid in class,” Fields said. “It can be weird because you can kind of feel the eyes on you, especially when you stand up and speak. It just took time like anything else.”

“It can be weird because you can kind of feel the eyes on you, especially when you stand up and speak. It just took time like anything else.”

Fields said he learned how to adapt and adjust to different situations at Cal Poly — something he said he worked on unconsciously every day just by walking through campus. However, despite Cal Poly’s lack of representation, the standout point guard also said he is glad he chose to attend the university. If he had the option, Fields said he would not reconsider coming to Cal Poly.

“In life, in order to be able to grow, you need to put yourself in uncomfortable situations,” Fields said. “For me, if I would have went somewhere where I was comfortable, I probably wouldn’t have grown as much as I have here.”

As a student athlete, Pressley said the racist events that took place last April distracted from the two aspects of life he chose to attend Cal Poly for in the first place. However, he credits Men’s Soccer head coach Steve Sampson with best teaching him how to deal with distractions in college.

“At the end of the day, we came here to get an education, and we came here to play soccer,” Pressley said. “It’s trying to figure out, ‘Hey, what do you want to be known for in college and how are you going to go about that? How are you going to be disciplined when other things all around you are falling apart?’”

Like Fields, Pressley said he enjoyed his time at Cal Poly as well. However, he also recognized those who did not have the same experience. Pressley said a couple students who lived in his residence hall freshman year ended up leaving as a result of the university’s lack of diversity.

“There were times where it wasn’t fun and it was like, ‘Ah, this school is super white,’” Pressley said. “But there were also times where you had a blast. Some of your best friends are here … I will give Cal Poly that. Despite the racial issues they’ve had, I have had a great college experience, and I wouldn’t change it for the world.”